Using your company's influence to drive change

Many of the most severe human rights issues faced by large companies are complex ones. Eradicating modern slavery and conflict minerals from supply chains. Preventing misuse of new technologies. Achieving meaningful progress on gender, race and other inequalities.

Often, the problem isn't simply that one person or one organisation did the wrong thing. Instead, these challenges can be deeply rooted in a much bigger picture, involving many different stakeholders.

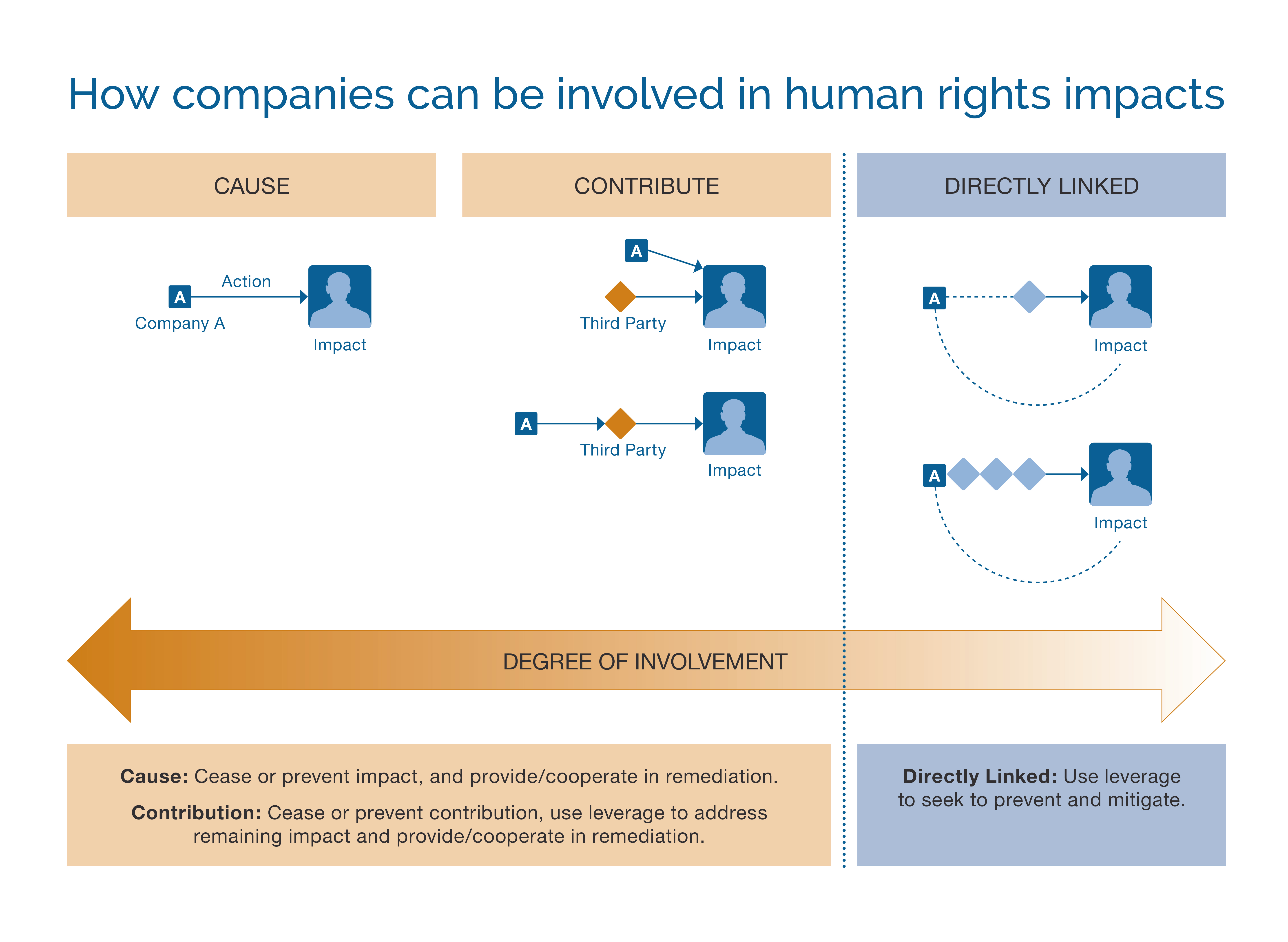

Many – even most – companies become involved in complex human rights challenges like these through their business relationships. If your company isn't causing or contributing to the problem itself, you may not be able to fix things. But stakeholders and international standards now expect you to do something. That is, to use your company’s influence – also known as leverage – to encourage others to act.

What does using influence – or leverage – look like in practice?

Ways to build leverage with partners:

- Integrate human rights into due diligence processes to assess human rights risks early, at the outset of the relationship.

- Make operating with respect for human rights “business critical” for partners by integrating it into negotiations and decisions.

- Build longer-term business relationships to shift mindsets and know-how over time.

Ways to use leverage in business relationships:

- Engage privately with business partners when things go wrong to understand the problem and develop a response.

- Collaborate with key stakeholders to build a shared understanding of the issue and agree ways forward.

- Take collective action, including at an industry level, to set common standards and strengthen coordination.

What do the UN Guiding Principles say about leverage?

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, or UNGPs, expect that where a company is involved in an adverse human rights impact through contribution or direct linkage, it will use its leverage in the relevant business relationship(s) seeking that the impact be addressed.

In other words, when something goes wrong, and a company is involved through its business relationships, it should do something - even if it can’t fix the problem itself.

Key guidance on using leverage includes:

- Appropriate action will vary according to the way a company is involved in an impact (cause, contribute or direct linkage) and the extent of its leverage to address the impact. The more complex the situation, the stronger the case for drawing on independent expert advice.

- If a company has sufficient leverage, it should use it to the greatest extent possible. Leverage is considered to exist where a company has the ability to effect change in the practices of an entity causing a harm. If it lacks leverage, there may be ways to increase it.

- A company should consider ending a relationship where it lacks sufficient leverage and is unable to increase its leverage. But it should take into account the potential human rights impacts of doing so.

- A company is not linked with every adverse impact associated with a given business relationship. The mere fact of a business relationship with an enterprise involved in human rights impacts is not sufficient to give rise to a direct linkage. There must be a linkage between the impact the the company's operations, products or services.

See the Commentary to Guiding Principle 19 and The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights: An Interpretive Guide for more.

Insights from business practice

-

Key standards are pragmatic, but creativity and effort are expected

The UNGPs' approach to leverage reflects principled pragmatism. That is, the principles recognise that companies need to find practical ways to drive change by using leverage. But the UNGPs and stakeholders also expect companies to be creative, and to build and use leverage in different ways to achieve meaningful outcomes.

The starting point in the UNGPs is the adverse impact – a company’s responsibility is not defined with reference to its proximity to the impact or the practicality of taking action. However, some companies find it helpful to focus first on what is practical. These initial steps may not align fully with what the UNGPs or stakeholders expect. But companies can build on what is learnt over time.

-

Companies now need to use leverage in a wide array of business relationships

These include minority and majority joint venture arrangements, sponsorships, franchise relationships, licensing, host/home government contracts and ownership of other enterprises. These relationships are often characterised by complexity – multiple, non-linear business relationships that exist simultaneously between two or more companies. And each relationship will have its own dynamics around influence/leverage.

For more on business relationships, see: Managing business relationships

-

The nature of leverage over suppliers, customers and other business partners is context-specific

It varies widely with the nature of the business relationship, the industry, domestic regulatory realities, state investment and growth priorities, and much more.

The unique characteristics of the company and of the business partner are profoundly important. These include organisational culture, ownership structure, commercial strength or vulnerability, business model adaptability etc. Further, the nature, length, terms and conditions underpinning business relationships are significant. It is not always easy, or even possible, to change/enforce these quickly. Leverage almost always requires collective action where a company is linked to situations beyond a first-tier relationship – but this is only possible if other stakeholders are willing to act.

-

Situational analysis is important

Situational analysis is necessary to understand if a company has a responsibility to use leverage and, if so, what action to take.

It is also needed to assess whether the company’s use of leverage and any other mitigating actions have been effective. In other words, it can be futile – and not good risk management – to make assessments from afar because the situation will likely contain many variables and complexities.

-

Establishing, increasing and using leverage takes time - it can improve a situation, but rarely fixes a problem

Establishing and increasing leverage in business relationships can be a long process – years, often, rather than weeks or months. Even where leverage is well-established, it can take significant time to achieve positive outcomes. Further, the UNGPs recognise that, in direct linkage and contribution situations, a company is not solely responsible for the adverse impact because it cannot fully control actions and outcomes on the ground.

It follows that even where companies apply leverage in serious and thoughtful ways, better human rights outcomes could be partial, tenuous and even fleeting. The time needed to achieve meaningful change using leverage can be especially challenging when there are severe impacts that require a rapid response.

-

It can be important to stay in a business relationship to try to achieve change over time

Thoughtful business practitioners advocate this strongly, even when leverage has been ineffective. Sometimes it is a matter of commercial drivers/constraints – for example, where the business partner supplies goods or services that cannot practicably be obtained elsewhere. But it can also result from commitment to driving progress in the long term. Ending a relationship relieves the pressure on both parties. But it also achieves little or nothing in terms of building awareness and commitment, and shifting mind-sets and practices, over time.

Where there is not a first-tier relationship between the company and the entity causing the harm, it may be impracticable to terminate as there is no “relationship”, as such, to end.

-

Effective communication is critical to navigating the complexities and ambiguities of direct linkage situations

In direct linkage situations, communication appears to be important in a number of ways. For example, it can be critical to building a shared understanding of the problem (including relevant details, dynamics and complexities). It enables shared expectations to be developed about what change is needed/possible and how to achieve it. Where a company stays in a relationship to promote change over time, communication can also help manage the reputational risks of staying in the relationship to influence behaviour longer-term. However, it seems to sometimes be difficult for companies to communicate “in the moment” with stakeholders about direct linkage situations.

Case study on using leverage: How Trafigura is working to address challenges in artisanal small-scale mining (ASM)

Looking forward: catalysing change across value chains

Companies' use of leverage can transform how we think about, understand and build solutions to the most pressing human rights challenges.

Real progress has been made to explore how to put this into practice. Yet we have only scratched the surface of what could be achieved. There are many more challenges to unpack. The consequences of different approaches also need to be better understood.

Places to start include:

Strengthening shared understanding of complexities: We need to better understand the complexity of global value chains and business relationships. Could each industry develop an infographic showing a typical value chain to help everyone understand how that industry works? See how Trafigura approached this in Commodities Demystified: A Guide to Trading and the Global Supply Chain.

Initiating dialogue about theories of change: We need more dialogue about what outcomes are "ideal" - and what interventions will achieve them. Collective action could be strengthened by agreeing who needs to be involved and what needs to be done – which could also lead to smarter allocation of resources. How could such dialogues be convened, and who should do this?

Building consensus around effectiveness and what “good” looks like: We need more evidence of the effectiveness of particular actions. We also need consensus about what good looks like. How should we assess outcomes and effort when multiple stakeholders are involved in solving a problem?